There can’t be just one single definition of ‘digital library’, as the concept has been on the move, developing, transforming since its (untraceable?) origins. That is how it is supposed to be, anyway: by digital, we want to mean available, indexable, searchable, open-ended, endless in content or possibilities or both. When referring to the history of digital libraries (some 20 years old: old enough for it to have a history of its own?), Candela, Castelli & Pagano talk about the early digital library as ‘the digital counterpart of traditional libraries’, which with time has been widely explored and experimented with, to then become a ‘complex networked systems able to support communication and collaboration among different worldwide distributed communities’.

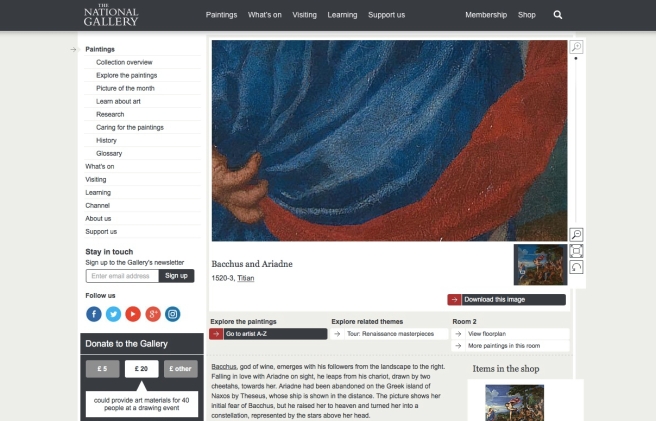

Evidently, a digital library must contain a managed collection. It was Valentine’s Day last week, and I was amazed to find out about the Museum of London’s ‘online collection’ of Valentines Cards—one of the quirkiest things I have ever seen. Over 1700 cards produced in London in the nineteenth century are part of the museum’s permanent collection, and this digitised version of it can be confidently said to be a ‘digital library’: a managed collection of digitised cards, containing matadata and search/advanced search service. I live close to the Museum, been there a few times, but had never noticed these cards. Maybe I was just too distracted, or maybe this digital library provided by the museum really enabled my deeper and further access to the objects and content they hold—even to me, who can easily go there in person. Also, note that this is a digital library from the Museum of London; physical limits and disparities between libraries, museums, archives, galleries, universities all become irrelevant when they talk about their collection of documents in the digital, online realm. This is the collection of digitised paintings from The National Gallery; go ahead and download a Titian or a van Eyck. Zoom in until you see the cracks on the canvases.

—

But are these digital documents surrogates or simulacrums? Jeffrey Drouin dived into the word ‘surrogate’ and its meaning to the digital world in the book Digital Keywords: A Vocabulary of Information Society and Culture. He defines a digital version of a document as a ‘surrogate in that it stands in for a print original (at least to the degree print texts may be considered originals)’; it is a ‘digital edition’. On the other hand, a simulacrum, well known to those who study the arts, is defined by The Oxford English Dictionary as the image which possesses ‘the form or appearance of a certain thing, without possessing its substance or proper qualities’; it is a ‘mere image, a specious imitation or likeness, of something’. Drouin then concludes that a simulacrum ‘fulfils the role of surrogate as a substitute deputed by authority yet lacks the true substance of that for which it stands’.

Then, again: when we digitise a painting by Titian, a nineteenth century Valentine card, or a manuscript, are we creating mere simulacrums? Drouin asks: ‘Is the data output of the digital surrogate fundamentally separate from the object from which it derives?’. He beautifully calls the digital surrogate an effigy: ‘the image of an original simultaneously worshipped and desecrated in the act of interpretation’. Perhaps, when digitising a document and making it available online, we are just setting free the idea of it.

—

‘The World Wide Web is not a library’. It may have ‘the scope of a comprehensive library, but it lacks a library’s rules of access and privacy’, Abby Smith Rumsey points out in her book When We Are No More: How Digital Memory Is Shaping Our Future. She talks about how the old paradigm of preserving the medium so to be able to preserve the message/memory/information—a manuscript, a letter, negative films—has shifted after the digital transition: we now need as much redundancy as possible, because digital data is the most fragile kind of information we have invented so far. What happens when the memory of us is all in digital data? How will and should libraries deal with a world of documents, our legacy, that is in bits and bits alone? Can we use the World Wide Web in our favour when it comes to ensuring free access to our information, as individuals and as humans?

Rumsey is optimistic:

Today, we see books as natural facts. We do not see them as memory machines with lives of their own, though that is exactly what they are. As soon as we began to print our thoughts in those hard-copy memory machines, they began circulating and pursuing their own destinies. Over time we learned how to manage them, share them, and ensure they carried humanity’s conversations to future generations. We can develop the same skills to manage and take responsibility for digital memory machines so they too can outlive us.

—

Digitisation is not the same as transforming into data, which we could call Datafication. In Big Data: A Revolution That Will Transform How We Live, Work and Think, Viktor Mayer-Schonberger & Kenneth Cukier draw the line between the two: while the digitised page of a book, for example, is an image ‘that only humans could transform into useful information by reading’, the further datafied version of it would be ‘usable not just for human readers, but also for computers to process and algorithms to analyze’, turning text into ‘indexable and thus searchable’ information.

Google has used both the digitised and datafied versions of the millions of books it scanned as part of its Google Books project. The digitised versions of the books, mutilated because of copyright rules, build up the digital library that Google Books is; the datafied versions, fully available for Google only, can be partly used through Google Ngram—‘When you enter phrases into the Google Books Ngram Viewer, it displays a graph showing how those phrases have occurred in a corpus of books over the selected years’. I’ve tried searching for the terms ‘women’ and ‘men’ in books in English between 1800 and 2000. The results for terms are usually quite interesting, but you really have to take your time and hard thought to be able to get anything out of it, to get to real conclusions, valuable, usable information.

It makes you think of what kind of incredibly large and powerful computer is needed to be able to go through millions of digitised and datafied images and come up with these kind and amount of data. It makes you think of magic, but magic is actually just illusion, after all—the illusion of a real world entirely readable through science.

—

References:

Candela, L., Castello, D., Pagano, P. 2011. History, Evolution and Impact of Digital Libraries. DOI: 10.4018/978-1-60960-031-0.ch001. In book Iglezakik, I., Synodinou, T-E., Kapidakis, S. (eds.) E-Publishing and Digital Libraries: Legal and Organizational Issues. IGI Global. pp.1-30.

Drouin, J. 2016. Surrogate. In book Peters, B. (ed.) Digital Keywords: A Vocabulary of Information Society and Culture. Princeton University, Princeton.

Google Books Ngram Viewer. https://books.google.com/ngrams. Accessed 20/02/2017.

Mayer-Schönberger, V. & Cukier, K. 2013. Big data: a revolution that will transform how we live, work and think. John Murray, London.

Rumsey, A. S. 2016. When We Are No More: How Digital Memory Is Shaping Our Future. Bloomsbury, London.